History - The Hotel’s Heritage & the Battle of Isandlwana

Isandlwana Lodge is an authentic Zululand destination that pays homage to a great South African heritage, the Battle of Isandlwana.

The Clash of Clans – the Anglo-Zulu War

On 22 January 1879, these expanses of rugged savannah bore witness to an unforgettable military skirmish between the British and Zulu empires. This battle went down in history as one of the Zulu Kingdom’s greatest triumphs.

Prelude to Disaster

In 1877, the British set the intent to extend its imperial influence in South Africa by creating a federation of British colonies and Boer Republics. This would require complete control over Zululand, a warrior kingdom neighbouring Natal and the Transvaal.

In December 1878, Sir Bartle Frere, British high commissioner for South Africa, issued an ultimatum to Zulu King Cetshwayo. The Zulu Kingdom would be required to dismantle its military system within 30 days, pay compensation for alleged insults, and agree to full cooperation with the federation’s demands. Knowing that the move would spell disaster for the Zulu people, Cetshwayo refused.

On 11 January 1879

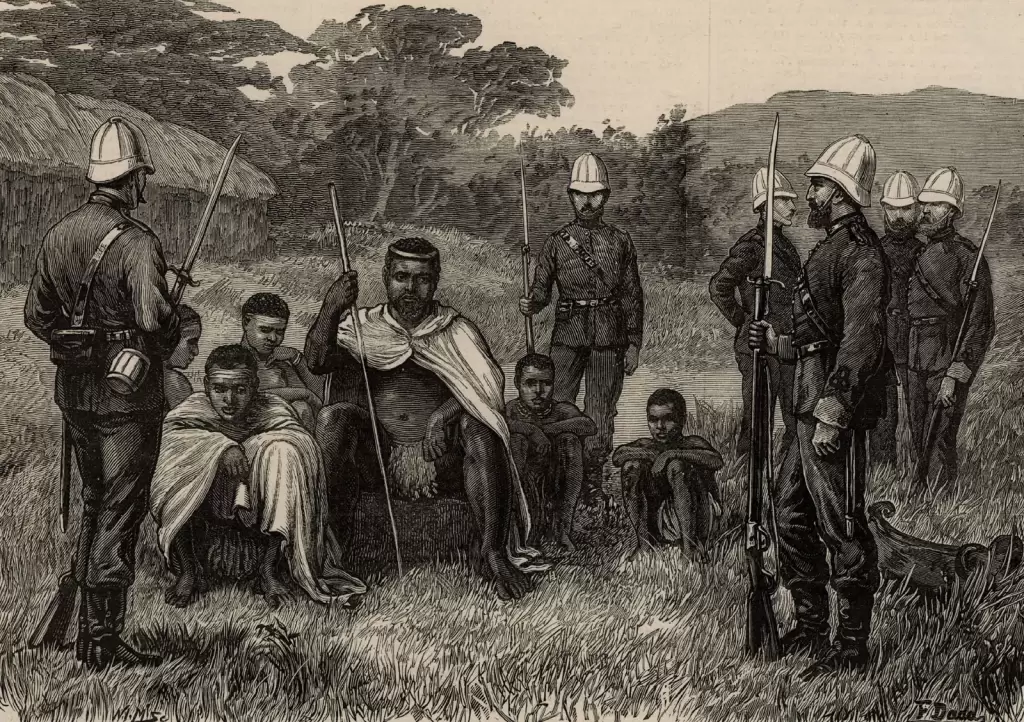

On 11 January 1879, the 30-day ultimatum issued to King Cetshwayo expired. A British Column crossed the Buffalo River at Rorke’s Drift, advancing into Zulu territory. On 12 January, British troops attacked Zulu Chief Sihayo kaXongo’s kraal, burned the kraal and food stores to the ground, and took possession of the chief’s cattle.

It’s believed that this action is what prompted King Cetshwayo to mobilise a military campaign against the British in the days to follow. The events’ timing was fortuitous, as many of the region’s warriors had already gathered for the annual First Fruit Ceremony (“Umkhosi Wokweshwama”) at Ulundi.

The Anglo-Zulu War had begun.

The Battle of Isandlwana

It was late morning on 22 January 1879. A British Column, advancing toward Ulundi, had set up camp at Isandlwana. A troop of British scouts encountered a group of Zulus and pursued them into the Valley of Ngwebeni. Mounting a hill, they were astonished to find the valley and its dongas filled with more than 20,000 Zulu warriors, waiting.

King Cetshwayo’s original strategy had been for the Zulu army to attack the British camps from the rear on the 23rd of January. With their position now compromised a day early, the Zulus had little choice but to fast-track their assault, and to directly target the camp at Isandlwana.

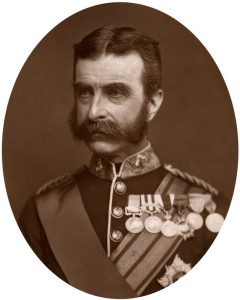

Lord Chelmsford

Adopting the late King Shaka’s formidable “buffalo horns” formation, the Zulu impi surged forward, charging after the scouting party and coming down on the British regiment at Isandlwana in full, mighty force.

Meanwhile, British numbers had been significantly diminished to just 1,700 soldiers, when commanding officer Lord Chelmsford took 2,800 men to pursue a small Zulu army – a crafty distraction designed by King Cetshwayo. What’s more, the British had failed to ‘laager’ the camp, which meant the troops could not form a defensive position in response to the Zulu attack.

The Zulu impi arrived swiftly, with the central column headed directly for the camp and the two ‘horns’ of the left and right column fanned out on either side, creating an almost-inescapable ambush.

Armed with short stabbing spears (‘Iklwa’), throwing spears (‘Assegai’), and shields, many Zulus initially fell as they charged, cut down by the British regiment’s powerful field artillery, Martini-Henry rifles and revolvers. However, as the horns of the Zulu impi and the central column closed in, the British advantage began to falter. Their ammunition gave out, and overly complex reloading

Armed with short stabbing spears (‘Iklwa’), throwing spears (‘Assegai’), and shields, many Zulus initially fell as they charged, cut down by the British regiment’s powerful field artillery, Martini-Henry rifles and revolvers. However, as the horns of the Zulu impi and the central column closed in, the British advantage began to falter. Their ammunition gave out, and overly complex reloading procedures resulted in precious moments of vulnerability. Wave upon wave of fierce Zulu warriors overpowered those who fought on with pistols, bayonets and knives, while many other soldiers fled toward Rorke’s Drift. Amidst the fray, and barely noticeable through the smoke and mayhem, a partial solar eclipse cast a foreboding shadow on the battlefield, peaking at 14h29.

procedures resulted in precious moments of vulnerability. Wave upon wave of fierce Zulu warriors overpowered those who fought on with pistols, bayonets and knives, while many other soldiers fled toward Rorke’s Drift. Amidst the fray, and barely noticeable through the smoke and mayhem, a partial solar eclipse cast a foreboding shadow on the battlefield, peaking at 14h29.

The Aftermath

The battle of Isandlwana lasted between four and six hours.

An estimated 1,400 British soldiers lost their lives. The Zulu casualties are more difficult to determine but are estimated at around 2,000 dead. The Zulus had achieved a landslide victory.

Many British survivors fled toward the Buffalo River, hoping to find safety within British Natal territory. Approximately 150 survivors gathered at Rorke’s Drift and successfully defended the station against an onslaught of Zulu forces the same night as the Isandlwana battle.

An undetermined number of survivors attempted to cross the river at what is known today as Fugitive’s Drift. However, the crossing was treacherous, and many were caught and killed by pursuing Zulu warriors. This is where Lieutenant Melvill and Lieutenant Coghill lost their lives trying to save the Queen’s Colours.

Panoramic Vistas of the Past

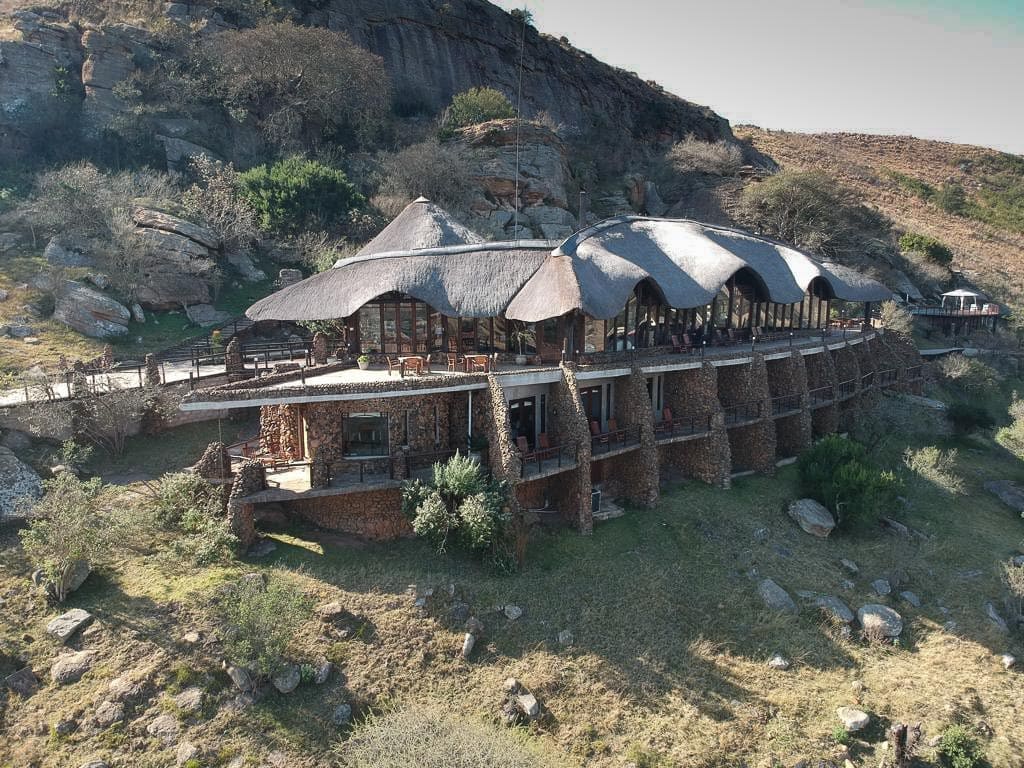

From almost every vantage point at Isandlwana Lodge, one has an unobstructed view of countless mounds of white rocks dotted across the not-so-distant landscape. Like stoic soldiers standing to attention, these stark monuments rise in honour of all who fell at Isandlwana – British and Zulu.

During the early- to mid-1990s, Tribal Councillors, Amafa Kwa-Zulu Natal, and The Mangwe Buthanani Tribal Authority negotiated a hotel site with foreign investors. In December 1997, a simple handshake with the Inkosi of the Tribe created the partnership that has brought jobs to the local community and will continue to bring revenue to the Tribal Trust for use in building schools, clinics and enhancing the life of villagers.

The Isandlwana Lodge vision was born.

Isandlwana Lodge was designed to appear as though it grew out of Nyoni Rock. In true Zululand fashion, the entire lodge is shaped like a shield, and built with rock and thatch to resemble the native’s kraals. The columns that support the roof are from the old West Street Pier in Durban, and each is named after a Zulu commander or significant person in the chain of command during the Anglo-Zulu War.

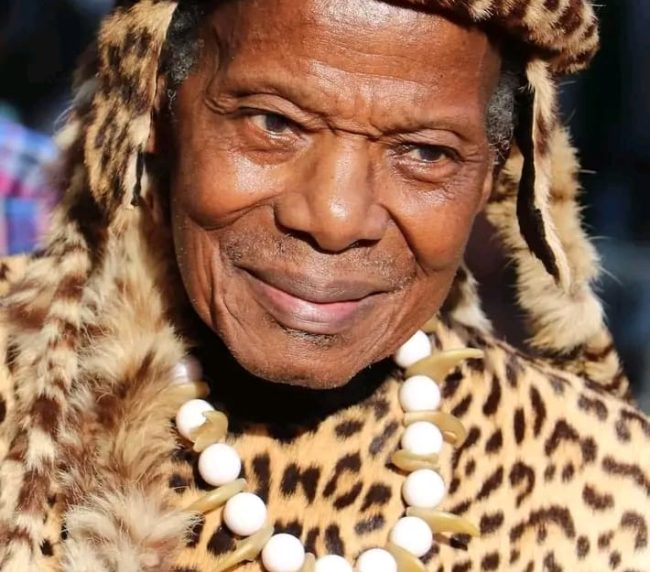

Throughout the lodge, details great and small pay homage to the battle of Isandlwana, and on 24 May 1999, the lodge was formally opened by Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, a direct descendant of King Shaka.

Isandlwana has hosted notable guests from across the world, including key figures from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain, Holland, Hungary, Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, South America, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand and the United States – and, of course, South Africa.

Plan your pilgrimage to Isandlwana Lodge and join the many thousands who have already journeyed into the pages of history.